Does It Hurt? Perception, Assessment & Treatment for Dementia Patients

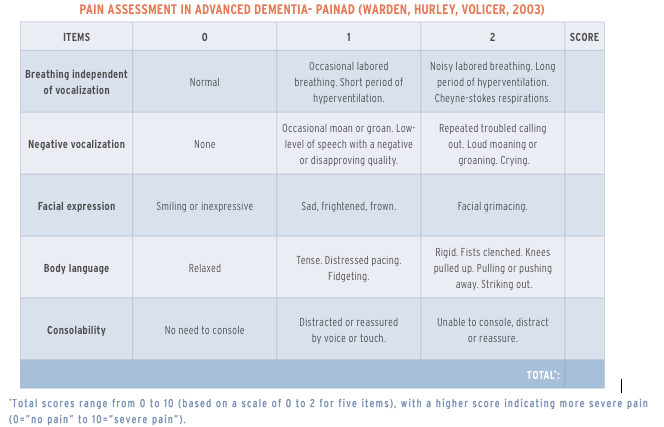

by Women's Brain Health Initiative: As people grow older, their risk of experiencing pain increases. The oldest population is hit the hardest, with pain prevalencerates of 72% among those aged 85 years and older. Given that dementia largely affects older adults, it makes sense that many individuals with dementia would experience pain, and it turns out that many of them do, despite not always being able to express their pain. One large study of more than 5,000 home-care patients found that there was no difference in the prevalence of pain among patients with or without dementia.The article “Pain Management in Patients with Dementia” by Achterberg et al., published in 2013 in Clinical Interventions in Aging, reports that approximately 50% of people with dementia regularly experience pain. It further indicates that among individuals with dementia who reside in care homes, 60 - 80% regularly experience pain, “most commonly related to musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal and cardiac conditions, genitourinary infections, and pressure ulcers.”The idea that damage in the brain prevents individuals with dementia from experiencing pain is a tragic myth.A study in Australia used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of 14 individuals with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and 15 age-matched individuals without AD (the control group) as they experienced pressure applied to the thumbnail of their right hands to induce varying levels of pain. The brain scans showed that pain-related brain activity was just as strong in the AD participants as in the control group. Although both groups experienced similar strength of pain-related brain activity, the pain activity lasted longer for those with AD.Differences in Pain PerceptionWhile we know from fMRI scans that the brains of individuals with dementia experience pain in the usual ways, other research suggests that there are differences in how those with dementia perceive pain. A Vanderbilt University study—published in BMC Medicine in 2016—examined pain responses in two groups of older adults (aged 65 and over): (1) healthy individuals and (2) people with Alzheimer’s disease who were able to communicate verbally. Both groups were exposed to different heat sensations and asked to report their pain levels. Participants with Alzheimer’s disease demonstrated a reduced ability to detect pain. In other words, it required higher temperatures for them to report sensing warmth, or to experience mild or moderate pain, as compared to the healthy individuals. However, there was no evidence that those with AD were less distressed by pain or that the experience was less unpleasant for them. Key questions remain such as are those with AD not as capable of perceiving pain, or do they perceive the pain but do not recognize and report it as pain?Pain Perception Varies by Type of Cognitive ImpairmentA review of research literature about the pain responses of individuals with cognitive impairment, conducted by Defrin et al. and published in the journal PAIN in 2015, found that in general, people with cognitive impairment, may be more sensitive to pain than cognitively-intact individuals, and the differences vary depending on the type of cognitive impairment. For example, the literature repeatedly indicated that the experience of pain is elevated in those with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, but pain sensitivity in a late stage of the disease is not clear. Pain responses also appear to be increased in people with Parkinson’s disease, but decreased in those with frontotemporal dementia and Huntington’s disease. The authors point out, though, that our current understanding of why these differences exist is limited.Pain is Under-assessed & Under-treatedPain is often under-assessed and under-treated in people with dementia, likely because of their altered pain experience and inability to self-report the pain (particularly in later stages of the disease). When their pain is not noticed or goes untreated, not only do they suffer unnecessarily, but it can also lead to other problems, including:Behavioural changes, some of which make caregiving more challenging. Pain is considered a frequent cause of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), such as agitation and aggression. This can lead to the prescription of inappropriate medication such as antipsychotics or antidepressants;Decreased mobility, leading to less independence and increased risk of falling;Missed opportunity to diagnose underlying health issues that could be causing the pain, such as urinary tract infection; andHastening deterioration of cognitive function. Studies have found that when people live with chronic pain, the volume of grey matter in their brains declines and the white matter is affected as well; the longer and more intense the pain, the more dramatic the changes to the brain. These changes may lead to faster declines in mental function.How to Recognize Signs of Pain in People with DementiaDo not wait for individuals with dementia to mention that they are in pain; rather, ask them if they are. Many people with dementia, especially those in mild or moderate stages, can accurately self-report their perception of pain. As dementia progresses, however, the ability to self-report pain generally declines. Patients who score below 15 on the Mini-Mental State Exam are generally considered too impaired to fully understand self-reporting pain scales. So, in later stages of dementia, observation is used to detect pain.“For those who are nonverbal, you can watch for behaviours and signs that can indicate pain,” explained Dr. Cary Brown, a professor in the department of Occupational Therapy at the University of Alberta, and co-presenter of an online workshop about pain and dementia for family members of persons with dementia (www.painanddementia.ualberta.ca). Dr. Brown suggests using a simple tool called PAINAD (Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia) to track your loved one’s potential signs of pain.The tool, available on the website, is a checklist with five items:Breathing; Negative vocalization; Facial expression; Body language; and Consolability.After observing your loved one for a short time, you simply mark off where your loved one falls on a continuum, scoring between zero and two for each item, then add up the total score out of ten. For example, under facial expressions, “smiling or inexpressive” gets a score of 0, while “sad, frightened or frowning” scores one, and “facial grimacing” scores two.“It is important to note that the PAINAD tool only helps identify the potential presence of pain. The final score should not be interpreted as an indicator of the severity of pain,” warned Dr. Brown. “The tool helps caregivers observe behaviours in an organized way and, if recorded in a pain journal, can highlight changes in one individual over time.”If you believe that your loved one with dementia is experiencing pain, advocate for his or her comfort by sharing your observations with his or her health care team. Continue with periodic observations and watch for changes in response to pain treatments or shifts occurring over time due to advancing age and disease. The health professionals will be using their own approaches and tools to assess pain, but no one knows your loved one like you do, and your supplemental observations can be very helpful as part of an overall pain management effort.Treating Pain“When family members believe that their loved one with dementia is showing signs of pain, there are several steps they can take immediately,” explained Dr. Brown. “First, look for and address any potential underlying causes of pain. For example, are their clothes comfortable or are seams perhaps rubbing on their skin? Are their shoes giving them blisters or corns? Do their glasses fit comfortably? Might they be experiencing some dental pain?”Family members can also try non-drug therapies to help alleviate pain such as gentle massage, applying hot or cold packs, gentle movement of the limbs, and relaxation. “These activities are safe to do even if someone is taking pain medication as well,” said Dr. Brown.Be sure to consult with a doctor to determine the best treatment approach for addressing your loved one’s pain. The doctor may identify and treat an underlying medical issue that is causing the pain, provide a referral for physiotherapy or acupuncture, or prescribe pain medication.When choosing pain medication for someone with dementia, a doctor must carefully consider the balance between benefits and risks. For example, some medications may interact with other drugs the person already takes, may negatively impact other health problems the person has, or may increase the risk of falling. The dosage may need to be higher than what a cognitively-healthy adult would take because some dementia-related changes in the brain can impact one’s response to analgesics. To add further complexity, doctors need to consider the ways in which pain medications affect the sexes differently. We already know that women and men can experience varying impacts and side effects when taking pain medication, but more women-focused research is needed to explore differences among women (i.e. if responses to pain medication vary depending on a woman’s age and whether she is pre-, peri-, or post-menopausal).Women Experience Pain Differently Than MenIn recent years, there has been much interest and research into the differences between women and men when it comes to pain. Each new study provides a piece of the complex puzzle, but a complete picture has not yet emerged. A 2013 review paper entitled “Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings,” published in the July 2013 issue of British Journal of Anaesthesia (BJA), provides a recent snapshot into what has been learned so far. It reports that the literature “clearly suggests that men and women differ in their responses to pain.” For example, women tend to exhibit increased pain sensitivity. When exposed to an increasingly painful stimulus in an experimental setting, women usually ask the researchers to stop sooner than men do. The paper also mentions that women are at higher risk for experiencing pain.Research by Ruau et al., published in the March 2012 issue of Journal of PAIN, is an example of a study that found sex differences in reported pain. This innovative research made use of a vast collection of electronic medical records. Researchers analyzed over 160,000 pain scores reported for more than 72,000 adult patients at Stanford Hospital and Clinics and discovered that women reported feeling more intense pain than men, with almost every type of disease.Brain scans have shown that different parts of the brain respond to pain, depending on whether you are a woman or man. A University of California, Los Angeles study published in Gastroenterology in 2003, involving 26 women and 24 men with irritable bowel syndrome, looked at positron emission tomography (PET) brain scans during mild pain stimuli. While there was some overlap in the areas of brain activation seen in the women and men, there were several areas of differentiation. The female brain was more active in limbic regions (emotion-based centres) while the male brain was more active in the cognitive/analytical regions. The researchers point out that there are unique advantages to each type of response and neither is better than the other.Why women are more likely to experience pain, and tend to feel pain more intensely than men, is not entirely clear. Sex hormones, as well as psychological and cultural influences, are thought to be potential reasons. Another potential influence was cited in a study conducted by Bradon Wilhemli, described in the October 2005 edition of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.Dr. Wilhemli discovered a difference in the number of nerve receptors (which pick up on sensation) in women versus men. While women had on average 34 nerve fibers per square centimetre of facial skin, men had only 17. Although this study provided important insight into why women experience pain more powerfully, there is certainly more to learn in order to fully understand what makes a woman’s experience of pain different from a man’s. Instructions: Observe the older person both at rest and during activity/with movement. For each of the items included in the PAINAD, select the score (0, 1, or 2) that reflects the current state of the person’s behavior. Add the score for each item to achieve a total score. Monitor changes in the total score over time and in response to treatment to determine changes in pain. Higher scores suggest greater pain severity.Note: Behavior observation scores should be considered in conjunction with knowledge of existing painful conditions and report from an individual knowledgeable of the person and his or her pain behaviors. Remember that some individuals may not demonstrate obvious pain behaviors or cues.Reference: Warden, V, Hurley AC, Volicer, V. (2003). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 4:9-15. Developed at the New England Geriatric Research Education & Clinical Center, Bedford VAMC, MA. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.Source: MIND OVER MATTER

Instructions: Observe the older person both at rest and during activity/with movement. For each of the items included in the PAINAD, select the score (0, 1, or 2) that reflects the current state of the person’s behavior. Add the score for each item to achieve a total score. Monitor changes in the total score over time and in response to treatment to determine changes in pain. Higher scores suggest greater pain severity.Note: Behavior observation scores should be considered in conjunction with knowledge of existing painful conditions and report from an individual knowledgeable of the person and his or her pain behaviors. Remember that some individuals may not demonstrate obvious pain behaviors or cues.Reference: Warden, V, Hurley AC, Volicer, V. (2003). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 4:9-15. Developed at the New England Geriatric Research Education & Clinical Center, Bedford VAMC, MA. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.Source: MIND OVER MATTER