How viewing art can help people with dementia

by Gail Kenning for Medical XPress:

The symptoms of dementia take on different forms and vary from person to person. Long before diagnosis, individuals and their family and friends may notice changes in behaviour, mood, and cognitive and physical functioning.

People living with dementia are often not able to carry out activities without support. Sometimes, simply going to the shops, catching up socially with friends, or going to the art gallery can require meticulous planning and coordination.

Friends often stop calling by simply because they do not know what to say or how to respond to the news of the diagnosis. Yet interacting with other people and engaging in leisure activities are pleasurable and contribute to quality of life. While dementia impacts cognitive functioning – so memory and judgement may be impaired – people living with dementia are able to feel pleasure and joy.

In 2006, The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York set up an art access program specifically for people with dementia recognising the beneficial impact of engaging with artworks. Shortly afterwards, informed by the work at MOMA, the Art Gallery of New South Wales ran a pilot program inviting people living with dementia to view iconic works in the gallery collection.

The program has since been further developed. Under the guidance of program producer Danielle Gullotta almost 1,000 people living with dementia can now attend the gallery annually and view artworks with the program facilitators. The facilitators have an in-depth knowledge of the artworks viewed, and have been given training by Alzheimer's Australia NSW and Art Gallery staff.

The artworks include iconic Australian works such at Eliot Gruner's Spring Frost; work in touring exhibitions such as Matisse and the Moderns, and works from the Archibald Prize exhibition.

Researchers at the University of Technology Sydney recently undertook an evaluation of the program. The primarily qualitative study, to be launched at the Gallery today, observed 21 participants as they travelled there and looked at artworks once they'd arrived. (A further group of participants and their family members and caregivers completed questionnaires.)

The study found that the program contributed to the quality of life of people with dementia by providing opportunities for them to experience "in the moment" pleasure as they looked at the art, and engaged with other people.

Participants laughed, smiled, and pointed at things they noticed in the paintings. Others reminisced about their experiences of growing up in the Australian bushland, or made associations from the paintings to events in their daily lives.

One participant, "Samuel," was able to engage with paintings in a sophisticated way, suggesting that Russell Drysdale's painting Sofala showed the "spirit of Australia".

The facilitator asked what words describe this painting and the rest of the group joined in suggesting, "deserted", "destitute", "loneliness", "failure". Others were happy to admire the colours, or to simply suggest that they thought the painting was "beautiful".

Participants in the study (and program) had a wide range of symptoms associated with dementia, from relatively mild episodic memory loss to more advanced symptoms, including loss of speech and impacts on their physical and cognitive functioning. Not all participants were able to verbally articulate their responses, but researchers were able to observe facial expressions and exclamations.

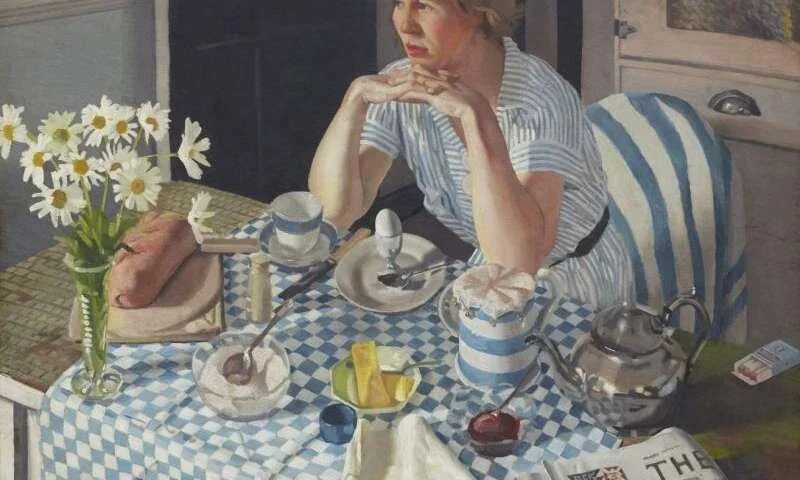

As a small group viewed Herbert Badham's Breakfast piece, they reminisced about times when they would formally set the table for lunch with a table cloth and napkins.

Other participants noted the painting has been made at the beginning of the second world war. The trained program facilitators, in turn, spoke of their joy in seeing people come quietly into the gallery and then suddenly "open-up and start talking".

The program provides opportunities for normalcy for people living with dementia. Normalcy in this context, means that each participant was treated with respect and dignity and recognised as having viewpoints that deserve attention regardless of their differing abilities.

This study did not focus on the long-term impact of art access programs on people with dementia – more research is needed in this area – but on the immediate experience of engaging with the artworks and people in the gallery space.

Many of the program participants may not retain long-term memories of the artworks they saw or the discussion that took place.

They can, however, benefit from the pleasurable experience of being in the gallery space, looking at the artwork and engaging with others and this can have an impact on their wellbeing after the memory of the event has gone.

Source: http://bit.ly/2cJW7tFPhoto: Herbert Badham Breakfast piece. Credit: Estate of Herbert Badham