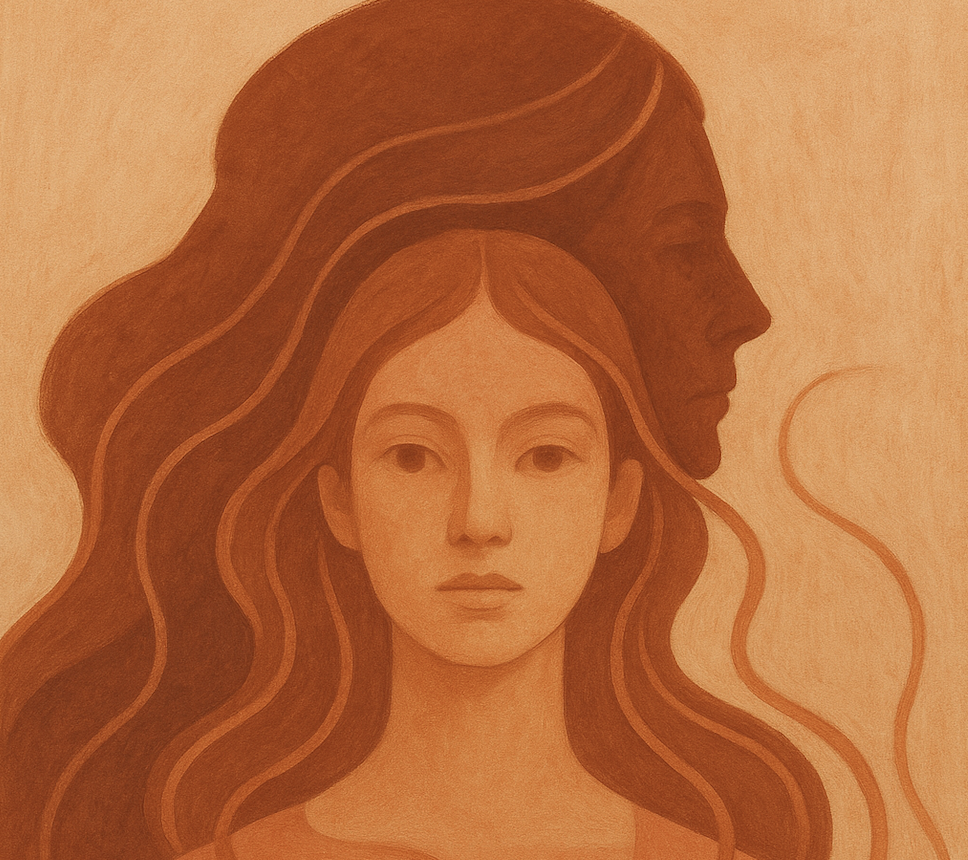

Not Your Mother’s Menopause

With Researcher Lucy Muir.

Lucy Muir’s interest in gender research was sparked far from any lab or institution of higher learning. It grew out of her experiences working at small-town radio stations in B.C. and Ontario, places where the attitudes and atmosphere left a mark.

“I witnessed a lot of ageism and sexism, especially against older women,” she said.

It set the tone for her academic career. In her undergrad studies at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) she wrote a thesis that explored gender discrimination in science.

Specifically, how research conducted by women tends to be judged harshly and treated as less important than research by men.

Ms. Muir also became interested in the social constructions of gender and aging and how they might affect cognitive health in older adult women. When the time came to pursue her PhD, her supervisor pointed her to the work on sex and gender being done by Dr. Gillian Einstein and colleagues at the Einstein Lab, which led to a successful application to join the team.

One of the lab’s main projects studies younger midlife women who have had their ovaries removed because of a genetic mutation that puts them at higher risk of cancer, and in particular, studies the impact of ovarian removal on their cognition.

Ms. Muir carved out a different aspect of the project to explore in her research study, which is titled, “Qualitative Experiences of Menopause Among Younger Women with Bilateral Salpingo Oophorectomy (BSO).”

As part of the larger project, women with BSO were interviewed about their experience of memory. However, Ms. Muir reviewed the transcripts and found that many of the participants, unprompted, commented on their experience with ovarian cessation, which was commonly referred to as “menopause,” since they were in their early 40s, years earlier than spontaneous menopause would occur if they still had their ovaries.

“This shows that menopause is a prominent experience that women with BSO want to discuss,” said Ms. Muir. While the results are still preliminary, she has found emerging themes that grow out of the experience of going into menopause after BSO.

“Menopause as a biological concept is one thing. But there’s a social component as well,” she said.

We have this image of what a menopausal woman should look like and act like. And (the study participants) have distanced themselves from that image. Some of them have said ‘I don’t feel like I should be in menopause. I’m not an older lady with white hair.’

“In other words, there is some disconnect between their body, their mind, and their social understanding of menopausal women. However, women who have undergone BSO, especially mothers, agree that menopause is a small sacrifice to prevent cancer and ensure that they can be there for their children.”

She hopes her study will help contribute to the bank of knowledge about women who undergo a life-preserving procedure with life-changing consequences.

“It’s not just a biological change, they’re also going through a critical social change,” said Ms. Muir. “It’s important to consider whether these factors might be affecting cognitive health. It’s important to ensure that they have support as they navigate the corollary outcomes of BSO.”

She also hopes to shed light on the experience of menopause more broadly. “In the popular imagination, menopause has derogatory connotations. There are negative stereotypes surrounding the idea of a menopausal woman. I hope my research will elucidate and reveal some of those stereotypes; ultimately, I want to consider how those stereotypes affect women in later-life menopause as well.”

As she works toward her PhD, Ms. Muir aspires to become a professor so that she can teach and continue research into the biological and social meaning of sex and gender. And she is grateful for the opportunity to work with Dr. Einstein.

“She’s a wealth of knowledge; the godmother of sex-and-gender research.”

Source: Mind Over Matter V21